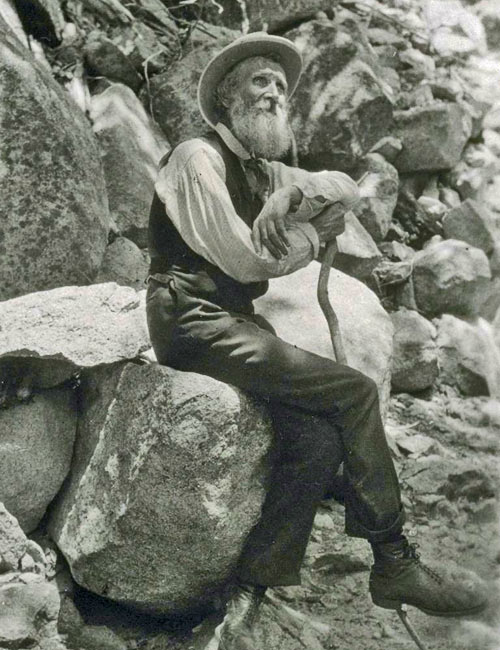

John Muir and the Mountain

By Gary VanDeWalker

Eight children raced through the Muir home in Scotland. John Muir was the third child, always looking for an adventure in nature. In 1849, his family moved to America, settling on a farm in Wisconsin. Muir grew up in the outdoors, pursuing the sciences in college, changing from subject to subject and never graduating. He ended up traveling in Canada to avoid military service. Returning to the United States, he took a job in a mill, where in an accident he almost lost his eyesight. He left to walk 1000 miles to Florida, vowing to make the pursuit of nature his life. A brief time in Cuba followed, and then he left there, setting off to see California.

On a fall day, Muir stood in California, gazing upon Mount Shasta, traveling in the clear weather between October and November storms, desiring to make a quick ascent of the mountain. He set out to travel from Redding to the inn of J.H. Sisson. The mountain grew larger, as its white base, gleamed in the sun. As Muir met other travelers, they warned him the mountain was too dangerous this time of year. However, Sisson indulged him, outfitting Muir for a snowy climb.

Muir’s love of climbing mountains began in Yosemite. He built a cabin and lived and explored the Sierras. He glimpsed Mount Shasta in 1873 when he came to work with the McCloud river salmon. He was tantalized by the white giant 80 miles north of where he was working. Muir wrote, “Shasta is a noble mark for a mountaineer, and I may soon reach it.” Between 1874 and 1914, his admiration turned into a dozen trips.

Despite the signs of an oncoming storm, Muir took a pack horse. He established a camp, making a bed of blankets to stay warm and be his base as he intended to make several trips up the mountain. The air carried a quiet stillness, which anticipated a tumultuous change in weather. His camp was on the upper tree line, where Muir planned to get up early, summit, and then descend back to his camp. At 1:15 am, he got up, eating a small breakfast, and he walked against the backdrop of the still open and starry skies. The only sound came from the crunch of snow under his feet.

The sunrise came with billowing puffs of clouds gathering around the mountain. The ice crystals hanging in the air made breathing a labor. He would sink often to his waist, sometimes crawling on all fours to make his way over the snowpack. His exhaustion was pushed off by the beauty surrounding him. Muir knew he was racing the storm. By 10:15 a.m. he won, reaching the summit.

For two hours, Muir observed the landscape surrounding the peak. He traced his vision through the paths of lava rivers, frozen around him. The wind challenged him, gaining intensity as if trying to push him from the mountain. Dark clouds would change the day to night as their ice crystals stung his face. It was time to descend.

He slept in his base camp, awakening the next morning to an endless site of the still gathering storm. Muir wrote, “A boundless wilderness of storm-clouds of different age and ripeness were congregated over the landscape for thousands of miles….” He took time he had left to gather dry wood and prepare for what was ahead. He prepared for a week of staying among his blankets. He gathered wood for snowshoes and waited until the first flakes began to fall.

The storm lasted a week. Sisson sent up horses to Muir, who returned admiring the newly flocked trees. Snowflakes were still falling, though at 4,000 feet rain replaced the snow. Sisson’s Station became Muir’s respite. He watched more snowfall.

Muir’s last ascent of the mountain was in 1875. His companions were Jerome Fay, a mountaineer and Captain A.F. Rodgers from the United States Coast Survey. This time, five feet of snow caused Muir to abandon the pack animals, and to have the three men carry their provisions to the timberline. They began their ascent at 3:20 a.m. the next morning and by 7:30 a.m. reached the summit.

As they descended, a brief rainstorm found them exposed. By noon, the small rain became a violent storm. By 3 p.m. the men felt the need to move lower down the mountain. The temperature dropped below zero, wind and lightning surrounding them. The daytime looked like night, as they worried about being blown away by the wind and began to fear freezing.

There are hot springs on Mount Shasta. Muir directed the men to make way to that location. The men laid in the warmth of the 1/8 inch mud. Keeping one side hot at a time. Two feet of snow fell on the landscape around them over the next two hours. Then as quick as it had formed, the storm broke. Muir asked Fay to entertain them with stories, so they could ignore the cold. They lay there for 17 hours regaining strength and anticipating the morning light. The three men would call out to one another, making sure each man was still alive.

As the daytime temperature rose, the men moved their frozen clothing as their limbs bent. They did not feel the warmth of the sun impact them until they were at 3,000 feet. Sisson could be heard shouting for them through the wood with horses to take them back to his hotel. They rejected food in favor of warm coffee. Upon hearing Muir’s tale, Sisson remarked that from the valley, only a small cloud cover could be seen on the mountain the day before. Snow gave way to green grass and flowers as they journeyed back to Sisson’s place.

Muir wrote of the end of that day’s journey:

At four in the afternoon we reached Strawberry Valley, and went to bed. Next morning we seemed to have risen from the dead. My bedroom was flooded with living sunshine, and from the window I saw the great white Shasta cone wearing its clouds and forests, and holding them loftily in the sky. How fresh and sunful and new-born our beautiful world appeared! Sisson’s children came in with wild flowers and covered my bed, and the sufferings of our long freezing storm period on the mountain-top seemed all a dream.

This article was posted originally at www.themccloudblog.com.